|

- |

- |

The

account following is not from Fulford's "Speculum Gregis". It is an

accompanying piece researched by David Ellison and included in his booklet "The

Rector and his Flock" published in 1980. |

- |

The

Croydon Farmers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A t

the time of the "Speculum Gregis", twelve tenant farmers supplied most

of the jobs in the parish of Croydon, but none farmed his own land. Mr J C Gape

(Lord of the Manor) leased his three Croydon farms to an agent (Withers), who

in turn subleased them; the Bursar of Downing managed the nine College farms himself,

carefully recording his decisions into the College minute books. Downing College

were seen to have been considerate landlords, if not astute businessmen. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The

rentals on Gape's farms worked out at about 15 shillings per acre, higher then

than on some local farms as late as 1950. From the advertisements which his agent

Withers printed when he was trying to dispose of his lease, we can obtain many

details of the farm buildings. For the £418 which he paid Gape annually,

he obtained Manor Farm, and the two farms at Croydon Wilds. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Manor Farm

was advertised as having "a pleasant two storey house with a porch".

There were then two parlours downstairs, with a kitchen, wash-house and dairy

behind; and four upstairs bedrooms. Outside there were three barns and another

'chaff and cutting barn', a cow house and a bullock house, two stables for ten

horses, a granary, cart shed, piggery and poultry houses. Two new cottages had

been erected for Pearman's two stock men, Blowes (page 82)

and Clark (page 81). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The farm itself

contained 350 acres, of which 65 were grassed down. After Abraham Pearman left,

Gape took the farm in hand himself, and sent a surveyor to examine the property

which was briefly occupied by a Mr Beale. Mowlson, the surveyor, noted that in

April 1844, there were 94 acres lying fallow and in tares, beans and peas; 128

acres of wheat, oats and barley; and another 44 acres of barley. Turnips have

not yet made an appearance in the rotation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The farmhouse

itself seemed to have become a little shabby - Withers had been responsible for

repairs. Mowlson said it needed "painting, whitewashing and colouring";

the kitchen needed a new oven; an upstairs back bedroom also required painting

and Beale had asked for the pump to be moved out of the house into the yard. He

also wanted a new shed there, and Mowlson agreed to pull down some old cottages

which had become "noisesome". Gape agreed that the work should be done.

[Sources: Cambridgeshire Record Office L 71.51 Valuation by I S Mowlson, Particulars

of Sale 296/SP 16, and the Cambridge Chronicle 21 May 1842.] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the north

of the parish, the two farms at Croydon Wilds were similar in size; both concentrated

on their arable. James Law at East Farm had only 33 acres of its 176 under grass,

and William Wilkins a mere 20 out of 174 acres. Other sale advertisements in the

Cambridge Chronicle show what crops were grown. Miss White, when she gave up her

father's farm at Tadlow Road, was only keeping 70 acres under the plough; she

had 20 acres of wheat, 27 of barley, 16 of peas and beans and 7 of tares. But

at the auction in September 1843 she put in 101 Leicester and Down cross lambs

up for sale, with 21 shearling and 65 store ewes "very fresh"; and she

had 2 sows and 25 store pigs. Like many other small farmers the dairy herd she

kept was only that which could be milked by one person, very probably herself.

She had 5 cows in calf, 5 heifers, 5 weaning calves and a "well-bred Shorthorn

bull". Milk yields would not then have amounted to more than 300 gallons

a year, and most of the milk was used to produce butter and cheese. Cambridge

was too far off for daily milk deliveries, and the villagers could not afford

it - they made do with skim-milk or whey. The pigs would probably end up in the

London market, as would the mutton, probably through the hands of a sheep jobber

(the local sheep jobber was William Pierce of Orwell who owned a cottage in Croydon).

[Sources: The Cambridge Chronicle 21 May, 22 July and

2 September 1842 and 13 April 1844.] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

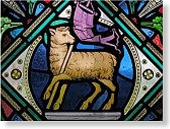

If Cambridgeshire

had a success story it was in the breeding of the new Leicester and Down Cross

sheep. At Babraham, twenty miles away, Jonas Webb specialised in the breeding

of this animal which had almost entirely replaced 'the common Cambridgeshire'

which Vancouver had reported at the end of the previous century; the annual sales

at Babraham were well known throughout southern England, and just two miles away

at Wimpole Hall the Earl of Hardwicke's Home Farm was virtually a model for the

county - well equipped and beautifully stocked. The Leicester and Down Cross was

saleable a year earlier, though some of the fine quality of the fleece was lost,

oddly enough because of the improved feed. Sheep troughs and hurdles figure in

nearly all the farm sales, along with dairy and brewing utensils. [Sources:

Charles Vancouver "A General View of Agriculture in the County of Cambridgeshire,

with Observations on the Means of its Improvement" pub 1794 pp 82-93, and

the Wimpole Home Farm inventory is in the Hertfordshire Records Office ref D/ECd/F104]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Samuel

George's farm was sold in 1844; for sale then were six "good working horses",

3 foals and a filly. Most farmers bred their own plough horses; some were well

heeled enough to have hunters, like Charles King, and the hounds met then, as

they do now, both at the Downing Arms in Croydon and the Hardwicke Arms

in Arrington. Also figuring in the items advertised were the carts and gigs, the

occasional chaise, a special lamb van and road waggons fitted with six-inch iron

shod rims, these paid less to go through the toll gates, since their broad wheels

broke up the road surface less. But mainly the carts were for dunging the fields.

Mr Haydon at Arrington, who went bankrupt in July 1842, had six.

[Sources: for Samuel George, the Cambridge Chronicle for 30 November 1844, for

Haydon the Cambridge Chronicles for 27 April and 14 September 1844.] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Haydon's at

Arrington is our last example. Several Croydon men walked the three miles thither

daily. He had had 150 acres under crops - 56 of wheat, 60 of barley, 15 of peas,

6 of tares and 10 of clover seed. Clover was a recent innovation. Some was dunged

for mowing as hay, and the rest generally fed to the sheep; a little was left

for seed. Haydon's bankruptcy was only one of many in the county; the Cambridge

Chronicle is full of sale notices, tenancy changes and even the curious notice

about the Croydon churchwarden, Chandler Merry, who took over Manor Farm. Just

before Fulford arrived there was this indication of the strain on the tenant farmers: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Chandler

Merry... attempted to put an end to this existence by cutting his throat with

a razor, and so far succeeded that his life is despaired of. The cause of this

melancholy event is, it is said, low nervous affection since the death of his

wife twelve months ago." [Source: Cambridge Chronicle

10 July 1841] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Merry's

depression had certainly lifted by the time Fulford arrived, for his entry (page

62) in the Speculum Gregis" shows him to have remarried a London lady, "very

civil and friendly". But Fulford remarks pointedly of William Ellis (page

88), nephew of the Tadlow farmer whose threshing machine caused the riot, that

he was "engaged to be married, but waiting for better times". How were

the better times to come? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Throughout

the length and breadth of England there were bitter argument over corn prices.

They had been high in 1839: at 70s 8d a quarter, higher than they had been for

twenty years. But a series of good harvests lowered the price to 50s 10d by 1845.

Proponents of repeal of the Corn Laws maintained that abolishing the duty of imported

corn would increase the country's true prosperity. What would the repeal of the

Corn Laws do to country districts like Croydon? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nearly all

the Cambridgeshire farmers thought it would break them. The Earl of Hardwicke

at Wimpole Hall led local opposition to their repeal, and even resigned his government

appointment; Croydon was among many parishes whose tenant farmers organised petitions

against repeal. When the Anti-Corn Law League came to Cambridge as the

campaign stepped up and Cobden held meetings in the city, counter-demonstrations

were put on. One meeting of tenant farmers passed a resolution deploring "the

unnscrupulous counduct of the dangerous society calling itself the Anti-Corn Law

League" and attacking its "nefarious designs". [Sources:

Samuel Jones "On the Farming of Cambridgeshire", "Journal of the

Royal Agricultural Society" vol 7. 1846, pp35 et seq, "Cambridge Chronicle"

10 July 1841, "Cambridge Chronicle" 29 May and 5 June 1841 and "Cambridge

Chronicle" 10 February 1844.] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In fact the

best of Cambridgeshire farming methods were very good, and proved to be well able

to withstand the shock of repeal which came the year after Rev Fulford left Croydon.

As 'Improvement' had come late to the county, many lessons had been learned. Samuel

Jones claimed:"Few counties have improved more than Cambridgeshire has lately

done,... We see now the land farmed on the four course system - the best that

could be adopted. ...Large flocks of sheep (not barely kept in existence, as heretofore)

are fattened with corn and cake, thus enriching the land, and increasing its productive

powers". [Source: Jonas, op cit] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Downing College's

rent books show that they ploughed back nearly half their gross rentals on improvements.

Buildings were kept in good repair, trees planted in the village and a modest

income obtained from the sale of elm and ash poles. Game was preserved, and a

woodman employed. Tenants were reimbursed for draining the heavier lands near

the Cam: Mrs Casbourn received some £25 for drainage in Sweet Mead. When

a freak hailstorm caused widespread damage throughout the county on the 10 August

1843, Mr Ellis (page 88) and Mrs Casbourn (page 74) both received rebates of £100

and £30 respectively. [Source: Downing College

Rent Books 1840-1844, Downing College Proceedings, Vol B, 1812-1860]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It

must have been quite a storm - the "Chronicle" reported that "many

windows were broken by large hailstones, some of which weighed a quarter of a

pound. Pigeons in large quantities were killed and livestock hurled into ditches

as if by a hurricane." The Church Register in nearby Wimpole recorded "A

most dreadful storm passed over this parish and caused the most serious destruction

of property. It began about 4 o'clock p.m. and lasted several hours - the lightning

and hail were terrific, the former like sheets of fire filled the air and ran

along the ground, the latter as large as pigeon's eggs; some larger and others

large angular masses of ice.... The destruction of property was dreadful! All

the windows on the north side of the Mansion [i.e. Wimpole Hall] were broken,

all the hothouses, and every window facing the north in many of the cottages!...

The storm entered from the north sea and passed through the land in a SW direction,

spreading ruin in its progress - "the land before it was as the Garden of

Eden, behind it a barren and desolate wilderness". The corn over which it

passed was entirely threshed out, boughs and limbs torn off the trees, pigeons

and crows killed, many sheep struck by lightning, and what the hail and lightning

did not utterly destroy, the rain which fell in torrents finished. Such was the

violence of the rain and its continuance that a stream rolled down Arrington Hill

four or five feet deep, washed men off their feet, and carried away 30 or 40 feet

of the Park wall. But amidst all this affliction God was merciful; no human lives

were lost, and the destruction of property, although grievous, was partial."

[Source: "Cambridge Chronicle" 12 August

1843, Wimpole Parish Registers CRO P179/1/2.] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Would Downing

College's improvement work enable Croydon to keep up with the threatened catastrophe?

Would the growing population outstrip the food grown? These were the fears of

the farmers; and Jonas, though an optimist, had some reservations about this area

of the county: "As you ascend the range of hills, you find the soil of a

thin staple and very poor, resting on a tough retentive tenacious clayey subsoil,

of very little depth, which has not yet been well-farmed. From Wimpole to Hatley

I found a large tract of country very badly cultivated, not only covered with

thistles, couch grass etc, but sadly wanting that first and great improvement

on heavy clays, viz, thorough draining. [Source: Jonas,

ibid] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How

to make the land pay best? One of the farmers had a solution noted by the Rector

just a little different from the others. "Old Larkins" (William Larkins

- page 61) "rents some land and is a cattle jobber and drover". He rented

from Downing College, paid a rental of £120 and used the land merely as

a holding ground for the herds of Scots and Yorkshire cattle brought south by

the drovers, first to the Huntingdon market, and then on to the London markets.

Some were sold on quickly, others kept to finish as stores and the few unfit to

travel further were butchered locally. It was a business which would thrive only

until the railway network linked north and south. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Farmers played

another role in the community - that of managers of the parish in local affairs

under the chairmanship of the Rector. They were not only employers, but administered

the parish roads, maintained law and order, and until 1834 they had tried to tackle

the problems of the aged, the sick and the poor. To do this, they elected annually

- if 'elected' is the right word among such a small group - a Surveyor of the

Roads, an Overseer of the Poor; and the Constable was as often as not one of their

employees, perhaps a foreman on one of their farms. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Work

in Progress) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- |

| © Copyright Steve Odell and the WimpolePast website 2002-2021. | |

|

- Contact the Website here. - All information on this web site is supplied in good faith. - No responsibility can be taken for errors or omissions. - This site does not use cookies. |

| All information on this web site is supplied in good faith. No responsibility can be taken for errors or omissions. This site does not use cookies. |